Views: 0

Preventing Blood Sugar Spikes May Help Reduce Acne

The Essential Info

A high glycemic diet is one that is, generally speaking, high in sugar/carbs and processed foods.

This type of diet leads to spikes in blood sugar levels which causes a cascade of hormones and inflammation that some scientists suspect may lead to increased acne symptoms.

A small collection of research now exists surrounding this idea, and while some of the research is contradictory, the preponderance of the evidence is pointing toward this being a real possibility.

Because the amount of evidence supporting the link between a high glycemic load diet and acne is growing, it may be useful for acne sufferers to try to eat a lower glycemic diet when possible. This means eating a diet rich in:

- Fish/Meat/Poultry/Eggs

- Vegetables

- Nuts

- Oils & other fats

It also means reducing the amount of high glycemic foods, such as:

- Processed foods

- White bread/White rice/White potatoes/Pasta

- Crackers/Pretzels

- Pulp-free juices

- Candy

- Soda

My Experience: Throughout the years, I have tried every possible way of eating low-glycemic and carefully monitored my skin as I did it. I tried eating strictly paleo for 2 months and it helped clear my skin, but not completely. I have also tried being strictly keto for 6 months and that also helped clear me up, but not completely. I even tried being strictly carnivore for 2 months, which also helped me clear up, but again, not completely. However, the science is compelling that keeping blood sugar levels in check by eating low-carb should theoretically help reduce acne and offer a host of other health benefits, so I still eat low-glycemic most of the time. But I also make sure not to get too obsessed with it. If I go to my cousin’s house and she cooks amazing Persian dinner with rice and desert, I’ll indulge a bit and then get back on the low-glycemic wagon the next day when I’m able to choose my own food.

Fun Tip: Drinking apple cider vinegar after a high glycemic meal may help reduce a blood sugar spike. You can buy it at any supermarket, and it could be a fun superhero that can fight blood sugar spikes. Ask your doctor if drinking apple cider vinegar is safe to use with any oral medication you are taking, and if you get the green light, feel free to mix 1-2 tablespoons of it in 8 ounces of water (add stevia if desired for sweetness) and drink it right after you eat high-glycemic food for a little added insurance against blood sugar spikes.

The Science

- Glycemic Index & Glycemic Load Defined

- The Studies: Research Connecting Glycemic Load and Acne

- Research Limitations

- How Glycemic Load Might Affect Acne

- The Bottom Line

Professionals within and outside the medical community have long believed that a person’s diet might affect acne.

Why else, some experts argue, would 9.4% of the world’s population at any given time have acne when some cultures, like the populations of Tanzania, natives of Okinawa Japan, Canadian Intuits, and South African Zulu populations have amounts hovering around 1%? Adding fuel to the fire, scientists have found that acne increases in these populations after exposure to a Western lifestyle, which includes diets consisting of processed foods, dairy, and simple sugars.1,2

As researchers have attempted to understand the relationship between dietary sugar and acne, increasing amounts of data have accumulated linking a high-sugar or high-processed carbohydrate diet to acne development. This type of diet is called a high glycemic diet.

However, due to the lack of large, long-term, controlled trials, scientists have been unable to definitively confirm the link between a high glycemic diet and acne. Therefore, doctors have not yet widely implemented diet as an acne preventative or treatment. Still, there is some evidence that shows us that a high glycemic diet may be connected with increased acne symptoms.

Let’s start by breaking down a high glycemic diet into its parts: glycemic index and glycemic load.

Glycemic Index & Glycemic Load Defined

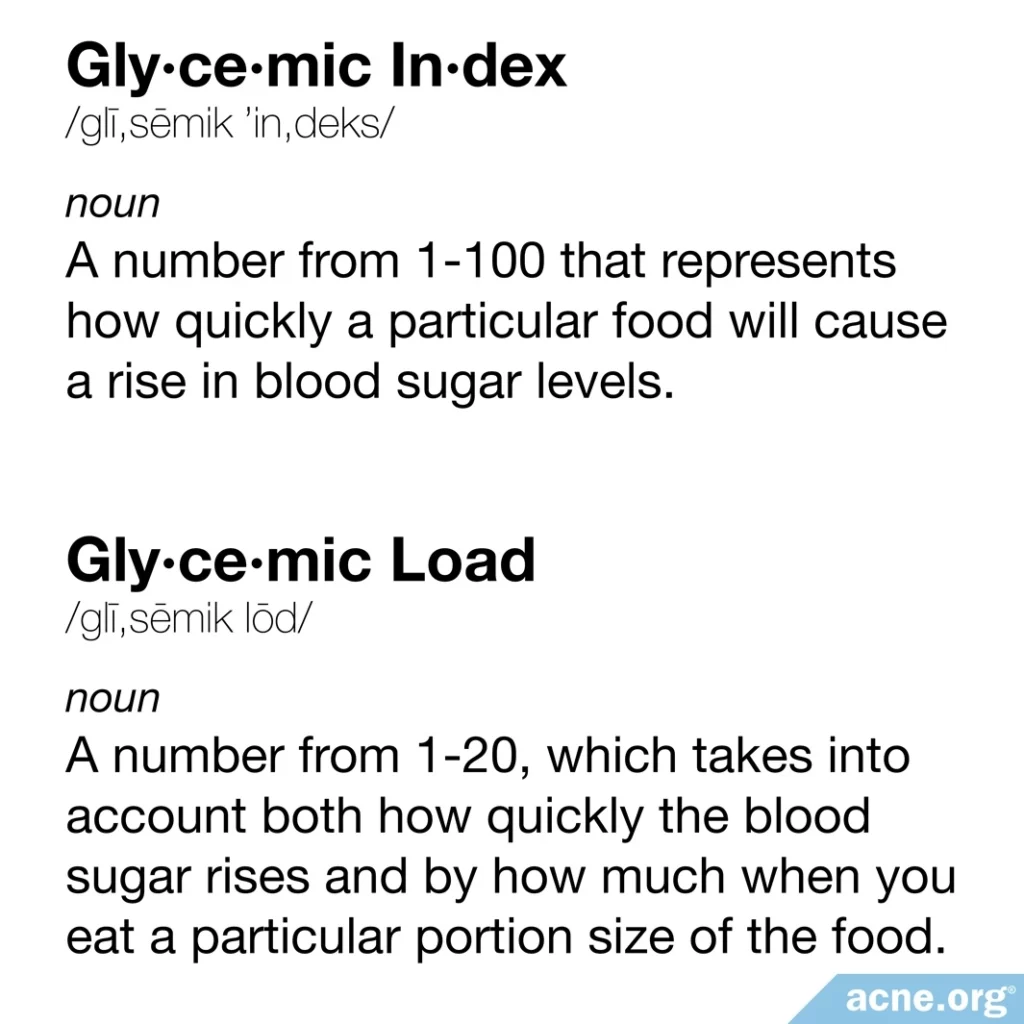

Glycemic index and glycemic load are two measures of a food’s ability to spike blood sugar levels. Although similar, each measures a slightly different capacity, and when it comes to acne, it is the glycemic load that is of concern.

Glycemic Index

The glycemic index (GI) is a number from 1-100 that represents how quickly a particular food will cause a rise in blood sugar levels.

When a person eats a food with a GI of 100 (e.g. glucose) it will cause an extremely quick spike in blood sugar, whereas eating a food with a GI of 1 (e.g. bean sprouts) will cause a very slow rise in blood sugar.3

Glycemic Load

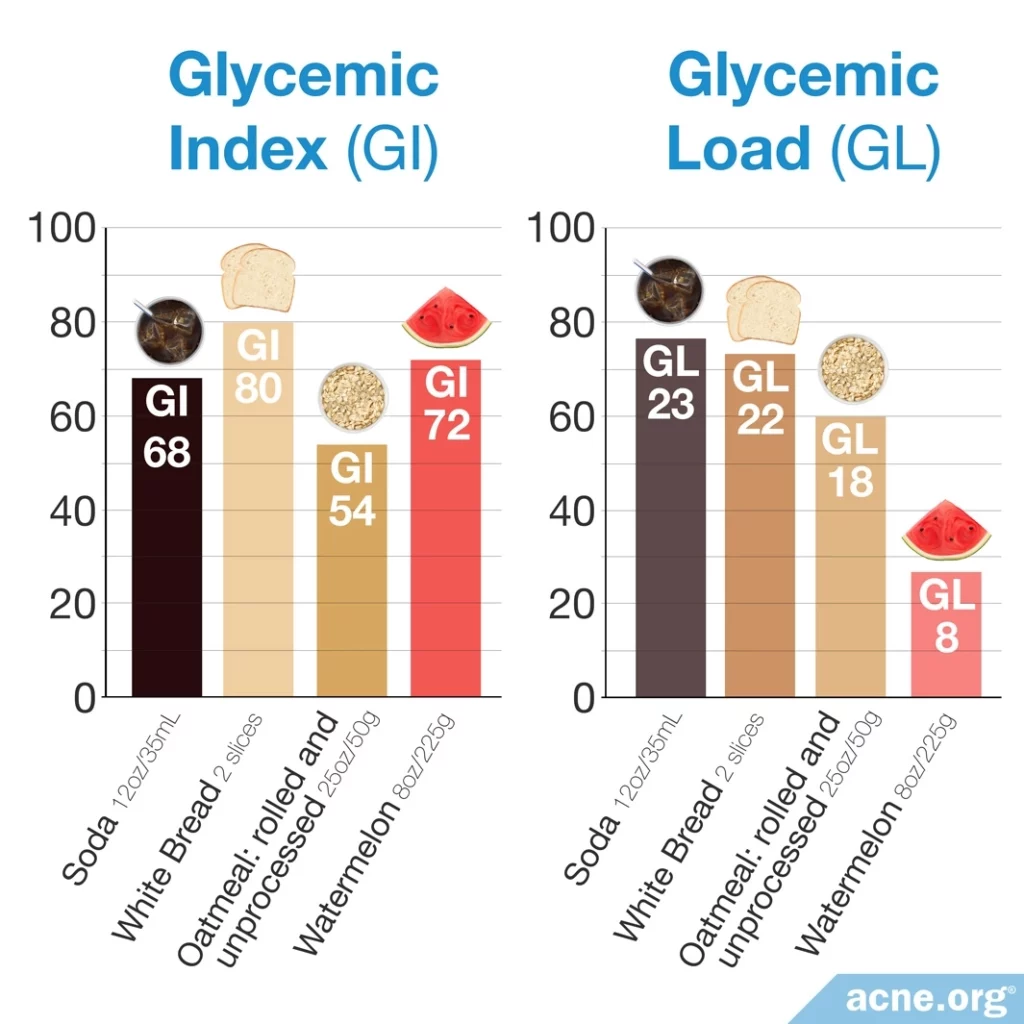

The glycemic index of a food only tells part of the story. It tells us how quickly the blood sugar spikes but not by how much – this is where the glycemic load comes in.

The glycemic load (GL) is a number from 1-20, which adds onto the glycemic index by taking into account both how quickly the blood sugar rises and by how much when you eat a particular portion size of the food.

For instance, watermelon has a high glycemic index (72), but a typical serving of watermelon does not contain a lot of carbohydrates, which means the blood sugar doesn’t rise by much, and therefore, the glycemic load is low.4

In other words, sometimes a food, like watermelon for instance, might have a high glycemic index, which means it makes blood sugar rise quickly, but has a low glycemic load, which means it does not cause the blood sugar to rise by much. Ultimately, what matters is how much blood sugar rises. Therefore, glycemic load is what we need to look at when it comes to acne.

Foods both high on the glycemic index and glycemic load include foods like soft drinks, candy, or bread, with large amounts of processed sugar or carbohydrates.

Foods both low on the glycemic index and glycemic load include foods like vegetables, meat, some fruits, and beans.

Foods high on the glycemic index but low on glycemic load include some fruits like watermelon and pineapple, and some vegetables like carrots and pumpkin. You might have heard that these foods are “bad for you” before because they have a high glycemic index, but they are not. They have a low glycemic load, which is what really matters.

The Studies: Research Connecting Glycemic Load and Acne

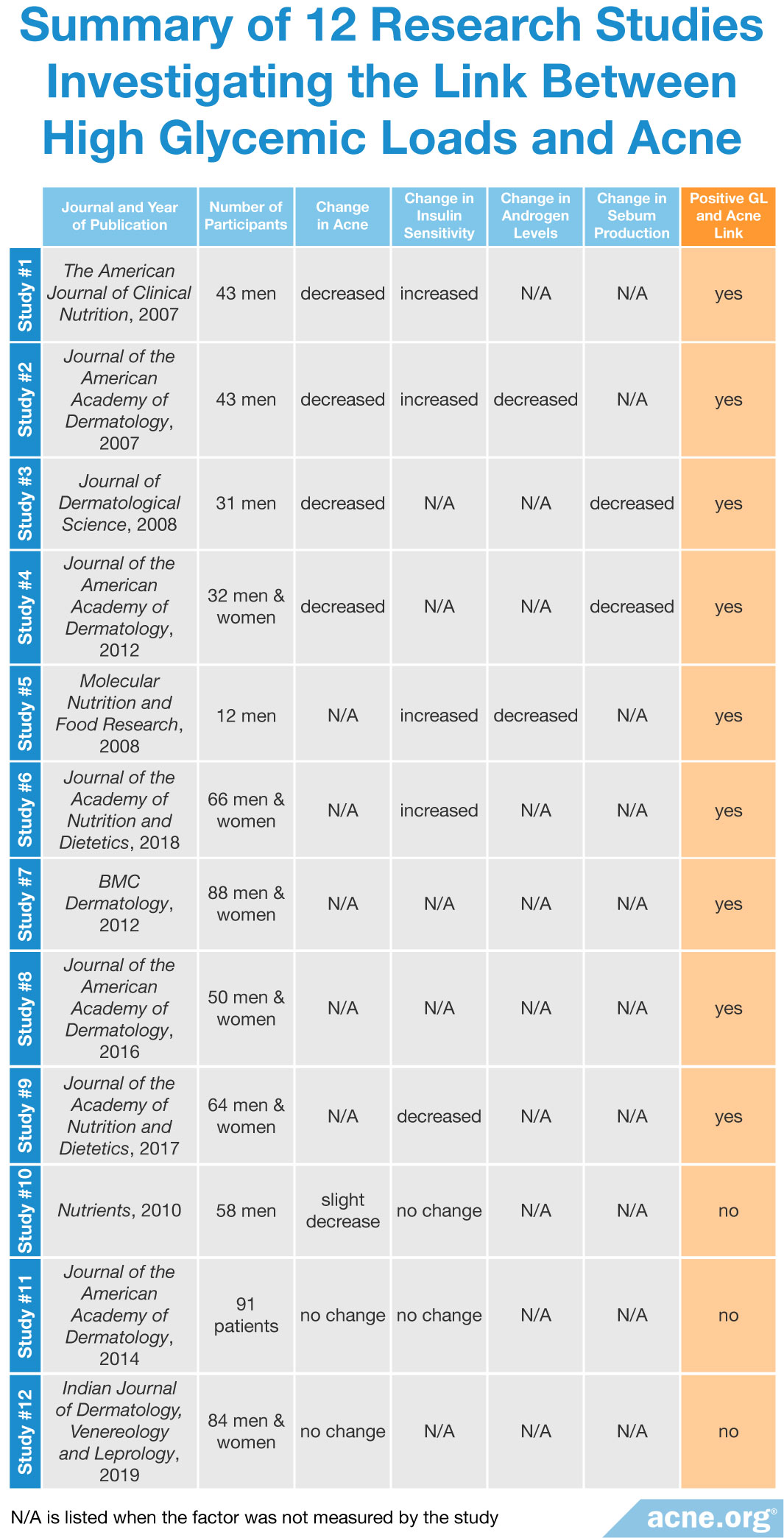

Scientists have performed 12 studies investigating the link between glycemic load and acne.

- 9 of the 12 studies concluded that a potential link between high glycemic load diets and acne development may exist.

- 3 studies found no such association.

So, the preponderance of the evidence at this point, albeit tentative, seems to point toward a connection.

Expand to read details of studies

Studies Showing a Link Between High Glycemic Load Diets and Acne

Nine studies conducted between 2007 and 2018 have found a link between high glycemic load diet and either acne or hormones in the blood that may lead to acne.4-12

Six of these studies observed benefits when placing people with acne on a low glycemic load diet for a period of 1-12 weeks. Four of the six studies found that a low glycemic load diet directly decreased the number of acne lesions and/or acne severity.4-7 Two of the studies did not look specifically at acne lesions, but noted that the low glycemic diet reduced hormone levels in a way that could lead to an improvement in acne.8,9

Three other studies did not try to change people’s diets, but simply compared the current eating habits of people with acne and people without acne. They found that people with acne tended to consume a higher glycemic load diet, which again suggests that there may be a connection between glycemic load and acne.10-12

Studies that placed volunteers on a low glycemic load diet and found an improvement in acne

A 2007 study published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition randomly assigned 43 men to two groups consuming either a high or low glycemic load diet for 12 weeks. After 12 weeks, the researchers concluded that the men consuming the low glycemic load diet had decreased numbers of total and inflammatory acne lesions, as well as an increased sensitivity to insulin, which is a hormone that the body employs to use and store sugars that it consumes. Greater sensitivity to insulin is good because that means that there is less sugar in the blood. Diabetics, who struggle with high blood sugar levels, are generally not sensitive to insulin.5

A 2007 study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology randomly assigned 43 men to two groups consuming either a high or low glycemic load diet for 12 weeks. After 12 weeks, the researchers concluded that the men consuming the low glycemic load diet had decreased the total number of acne lesions, increased sensitivity to insulin, and decreased levels of androgens (male hormones), which are hormones that cause an increase in sebum (skin oil) production.6

A 2008 study published in the Journal of Dermatological Science randomly assigned 31 men to either a low GL diet or a control diet with high amounts of carbohydrates. After 12 weeks, men consuming the low GL diet had decreased sebum production, and less total acne lesions than the men on the control diet.7

A 2012 study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology randomly assigned 32 men and women to a high or low glycemic load diet for 10 weeks. Patients consuming the low glycemic diet saw an improvement in acne severity as well as decreased sebaceous gland (skin oil gland) sizes.4

Studies that placed volunteers on a low glycemic load diet and found an improvement in hormone levels

A 2008 study published in the journal Molecular Nutrition and Food Research randomly assigned 12 men to consume either a high or low glycemic load diet. After one week, the men on the low glycemic load diet showed increased insulin sensitivity, lower androgen levels, and increased insulin growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) concentrations than men on the high glycemic load diet. IGFBP-3 is a protein that has two main functions: (1) to bind insulin growth factor-1 (IGF1) and (2) to stimulate skin cell death. When there are high levels of IGFBP-3, this binds to IGF1, which supports increased insulin sensitivity and stimulates skin cell death, which may decrease pore clogging.8

In a 2018 study published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the researchers randomly assigned 66 men and women with acne to follow either a low glycemic diet or their usual eating plan for 2 weeks. At the end of this period, the researchers found significantly lower IGF-1 concentrations in the volunteers who had been eating a low glycemic load diet.9 As we have seen, lower levels of IGF-1 indicate an increased sensitivity to insulin and potentially less pore clogging.

Studies that compared the eating habits of people with acne and people without acne and found a higher glycemic load in the diet of people with acne

A 2012 study published in the journal BMC Dermatology looked for a connection between people’s eating habits and acne. The researchers recruited 88 Malaysian volunteers (29 females and 15 males) between the ages of 18 and 33. Half of the adults volunteers suffered from acne, while the other half did not. By comparing the diets of the volunteers with and without acne, the researchers concluded that a high glycemic load diet may predispose people to developing acne.10

A 2016 study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology came to a similar conclusion. This study was conducted in Turkey. The researchers looked at 50 volunteers (22 males and 28 females) with acne and 36 volunteers (14 males and 22 females) without acne. The scientists asked the volunteers to keep food diaries over seven days and found a connection between high glycemic load diet and acne. However, the researchers stressed the limitations of the study, such as the short tracking of the volunteers’ dietary habits.11

A 2017 study published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics took a similar approach. The researchers looked at 64 volunteers in New York City: 32 adults (10 males and 22 females) with moderate-to-severe acne and 32 adults (7 males and 25 females) without acne. The volunteers kept food diaries for five days. At the end of this period, the researchers also performed blood tests to measure levels of glucose, insulin, IGF-1, and IGFBP-3. The scientists found that the volunteers with acne tended to consume a higher glycemic load diet than those without acne. In addition, the volunteers with acne had higher levels of insulin and IGF-1 in the blood. These findings support the notion that there may be a link between eating a higher glycemic load diet and developing acne.12

Studies Showing No Link Between High Glycemic Load Diets and Acne

Three studies conducted between 2010 and 2019 have found no link between glycemic load and acne.

In the first study, the researchers placed men with acne on either a high or low glycemic load diet for eight weeks and observed no significant difference in acne between the two groups at the end of this period.13

In the second study, researchers interviewed acne patients about their diet and used this information to categorize the patients as consuming either a high or low glycemic load diet. Again, the researchers found no difference in acne between the high and low glycemic load groups.2

In the third study, scientists asked people with acne who were using topical benzoyl peroxide to treat their acne to either eat a low glycemic load diet or follow their usual diet for 12 weeks. They found no difference in acne improvement between the two groups at the end of this period.14

A 2010 study published in the journal Nutrients randomly assigned 58 men to consume a high or low glycemic load diet for eight weeks. Although men consuming the low glycemic load diet saw greater improvement in acne compared to men consuming the high glycemic load diet, the improvements were not large enough to be considered statistically significant. Therefore, this study concluded that a low glycemic load diet did not result in acne improvements or increased insulin sensitivity.13

A 2014 study interviewed 91 patients about their dietary practices and then assigned them to either a high or low glycemic index group based on what they normally ate. After examining the patient’s acne severity, blood sugar, and insulin levels, the scientists concluded that there were no differences in any of the examined factors between patients consuming a high or low glycemic load diet.2

Similarly, a 2019 study published in the Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology compared the efficacy of a low glycemic load diet plus topical 2.5% benzoyl peroxide gel with that of only benzoyl peroxide gel in 84 male and female patients with acne. The authors did not find any significant improvement in acne in patients that followed a low glycemic diet for 12 weeks and applied benzoyl peroxide compared to those that followed their usual eating plan and used benzoyl peroxide.14

Research Limitations

Although nine studies have identified a potential link between glycemic load diets and acne, these studies are not proof that a high glycemic load diet causes acne.

This is because all those studies are small (less than 100 subjects) and have confounding factors like patient weight loss caused from the low glycemic diet. Weight loss can cause the body to become more insulin-sensitive and thus improve acne in the short term.

These study flaws, among others, prevent researchers from making a general conclusion about high glycemic diets and acne. Therefore, scientists will need to perform additional studies, including at least one large, randomized trial, in order to more definitively claim that high glycemic load diets cause acne.

However, for now, the evidence may point toward a connection. Let’s look now at the science behind exactly why a high glycemic load diet might increase acne.

The Science: How Glycemic Load Might Affect Acne

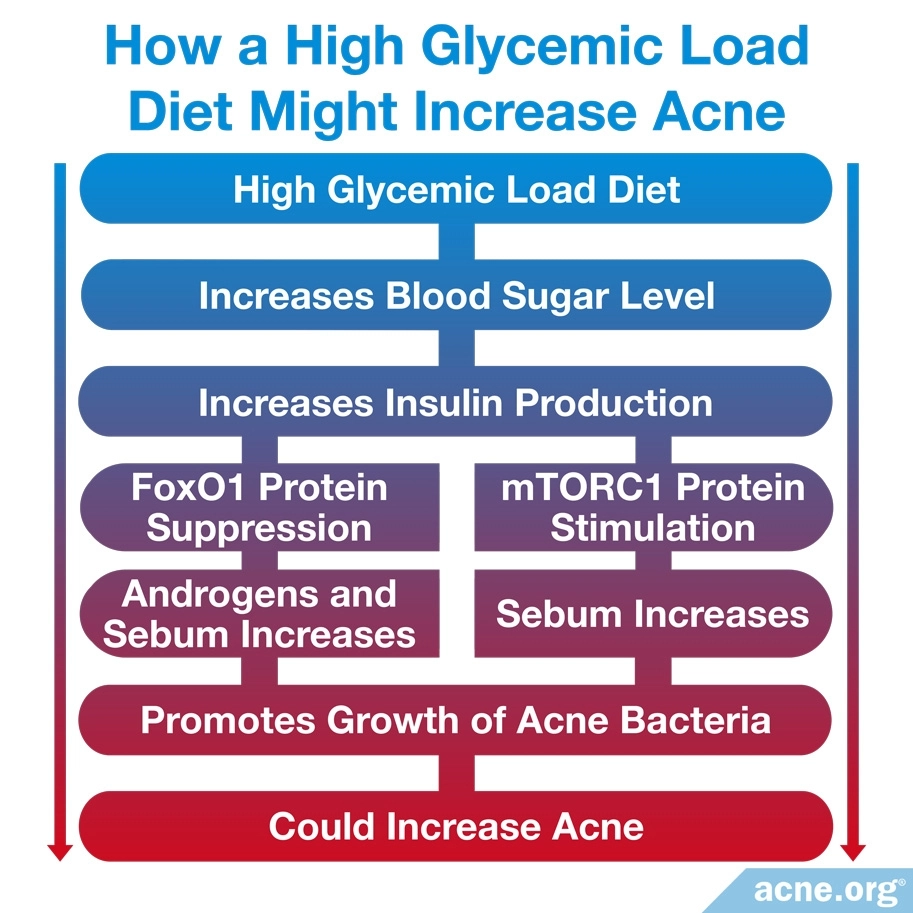

Eating a high glycemic load food increases the level of sugar in the blood. When the body senses there is a high level of blood sugar, it responds by producing insulin, which helps the body use and store the sugar. The presence of insulin then triggers the activation of a variety of responses in the body, which might potentially lead to an increase in acne.

Okay, here comes the deep science…One major response is the insulin-induced suppression of a protein known as FoxO1. The normal activity of FoxO1 is to inhibit androgen activity and also lower production of important sebum components called fatty acids. A rise in insulin leads to a suppression of FoxO1 and therefore increased androgen activity and production of sebum. A second major response to increased insulin is the insulin-induced stimulation of a protein known as mTORC1. The normal activity of mTORC1 is to promote the production of sebum. Therefore, a rise in insulin will increase the activity of mTORC1 and increase the production of sebum.1

Eating a high glycemic load diet leads to an increase of insulin, which suppresses FoxO1 and activates mTORC1 pathways. These pathways may result in an increase in sebum production, making the skin oilier, which could in turn promote the growth of acne bacteria. Therefore, some scientists predict that consuming a low glycemic diet will result in decreased levels of insulin and in turn a decreased amount of sebum, bacteria growth, and acne.15

The Bottom Line

Because it is so hard to study the effects of diet on disease, we still don’t know definitively whether eating a low glycemic diet will improve acne. But since the preponderance of the evidence points toward this possibility, and eating a low glycemic diet is healthy regardless, it can’t hurt to try to eat more unprocessed, whole foods whenever possible. While you should not expect a dramatic reduction in acne simply from changing your diet, consuming a low glycemic diet might help at least to some degree.

Eating low glycemic means eating more vegetables, whole fruits (not juice), nuts, beans, meats & fish, and unprocessed whole grains.

References

- Tan, J. K. L. & Bhate, K. A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne. Br. J. Dermatol. 172 (suppl.1), 3-12 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25597339

- Bronsnick, T., Murzaku, E. C. & Rao, B. K. Diet in dermatology: Part I. Atopic dermatitis, acne, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 71, 1039 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25454036

- Burris, J., Rietkerk, W. & Woolf K. Acne: the role of medical nutrition therapy. J. Acad. Nutr. Dietet. 113, 416-430 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23438493

- Zaenglein, A. L. et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 74, 945-973 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26897386

- Smith, R. N., Mann, N. J., Braue, A., Makelainen, H. & Varigos, G. A. A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86, 107-115 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17616769

- Smith, R. N., Mann, N. J., Braue, A., Makelainen, H. & Varigos, G. A. The effect of a high-protein, low glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: a randomized, investigator-masked, controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 57, 247-256 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17448569

- Smith, R. N., Braue, A., Varigos, G. & Mann, N. J. The effect of a low glycemic load diet on acne vulgaris and the fatty acid composition of skin surface triglycerides. J. Dermatol. Sci. 50, 41-52 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18178063

- Smith, R. N., et al. A pilot study to determine the short-term effects of a low glycemic load diet on hormonal markers of acne: A nonrandomized, parallel, controlled feeding trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 52, 718-726 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18496812

- Burris, J., Shikany, J. M., Rietkerk, W. & Woolf, K. A Low glycemic index and glycemic load diet decreases Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 among adults with moderate and severe acne: A short-duration, 2-week randomized controlled trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 118, 1874-1885 (2018). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29691143/

- Ismail, N. H., Manaf, Z. A. & Azizan, N. Z. High glycemic load diet, milk and ice cream consumption are related to acne vulgaris in Malaysian young adults: a case control study. BMC Dermatol. 12,13 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22898209

- Çerman, A. A., Aktaş, E., Altunay, İ. K., Arıcı, J. E., Tulunay, A. & Ozturk, F. Y. Dietary glycemic factors, insulin resistance, and adiponectin levels in acne vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 75, 155-162 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27061046

- Burris, J., Rietkerk, W., Shikany, J. M. & Woolf, K. Differences in dietary glycemic load and hormones in New York City adults with no and moderate/severe acne. J. Acad. Nutr Diet. 117, 1375-1383 (2017). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28606553

- Reynolds, R. C. et al. Effect of the glycemic index of carbohydrates on acne vulgaris. Nutrients. 2, 1060-1072 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22253996

- Pavithra, G., Upadya, G. M. & Rukmini, M. S. A randomized controlled trial of topical benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel with a low glycemic load diet versus topical benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel with a normal diet in acne (grades 1-3). Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 85, 486-490 (2019). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30264745

- Melnik, B. C. Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: an update. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 8, 371-388 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26203267

The post Glycemic Load Diet and Acne appeared first on Acne.org.